Asia Pacific

Malware top cyber threat for companies while ransomware risks grow - how risk managers can react

A compliance mindset and collaboration are key to dealing with a surge in cyber crime. Here’s what risk managers need to know

Our state of the industry survey reveals risk managers' top concerns for 2024

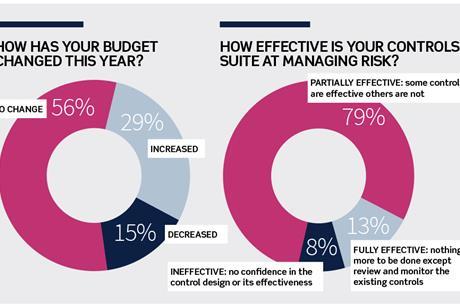

Our 2024 State of the Industry survey reveals a risk profession that is evolving, with more practitioners than ever moving beyond insurance buying to focus on enterprise risk management. But with new threats emerging at a dizzying rate, the pressure is on to improve controls and communicate your value. Sara ...

Health and safety tops risk concern list for Directors and Officers - here’s how to protect your business

Health and safety, cyber, and data loss are all key risks facing company directors and officers. To manage the threats, risk managers must focus on breaking down siloes and attaching dollar values to key threats

Why understanding the geopolitical rivalry over AI is business-critical

Technological rivalry around artificial intelligence is creating limitations on which systems can be deployed around the world and how they can be developed. Oxford Analytica’s Megha Kumar explains what businesses need to know

Case study: How Lendlease put people front and centre during the Fukushima nuclear accident and earthquake

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear accident and preceding earthquake and tsunami devastated the region in a matter of hours. Managing Lendlease’s risk response from the region, Kevin Bates describes putting a pause on other business concerns to focus on what mattered most – people.

SR Q1 2024: It’s tough out there, but we’ve got this

It sometimes feels like the world is spinning faster, as we are bombarded with ever-more complex and intertwining threats. It is the risk professional’s job to manage and mitigate, while guiding senior management through – no easy task. But with the right tools and information, we can do this.

Sector spotlight: how mining companies can manage growing ESG, regulation, and talent risks

There are few industries more at the coalface of steep risk management demands than the mining sector. ESG pressures, regulatory demands, and leaching talent are creating a challenging mix of exposures for its risk managers, writes Trevor Treharne.

Regulation watch: How to manage the risks created by the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act

Enhanced due diligence requirements set a new standard for supply chain management, Bindiya Vakil, CEO of Resilinc explores what the legislation means for risk managers

Spotlight on: the risks of doing business in china

Inscrutable new anti-espionage rules and opaque government processes set against a rocky COVID recovery and geopolitical tensions make risk management in China more crucial than ever. But it requires a creative approach and solid local connections. Trevor Treharne reports.

Technical briefing: risk management challenges in India

Rajeev Tanna, chairman of the IRM India Regional group and head of risk management and internal compliance at Tata Consulting Engineers shares the greatest risk management challenges for businesses operating in India in 2024

The heat is on: climate change set to increase economic losses

New research shows the economic impacts of climate change are set to get even more severe. Risk professionals must therefore urgently target prevention and mitigation measures.

Risk analysis: What will 2024’s elections mean for businesses

Risk professionals need deeper supply chain understanding and to think about how growing political risks might manifest, to weather the storm ahead

Spotlight on: Escalating NGO risks and how to tackle them

Against a backdrop of escalating threats, NGOs must prioritise the health and wellbeing of their workforces, including those in remote or unstable locations. Here’s how.

How ethical and compliance programmes can boost business performance

Over 60% of organisations have incorporated ethical behaviour into performance management, hiring, and reward practices. Here’s how to use ethics and compliance programmes to manage risks and improve business performance

Spotlight on: risks facing the financial services sector

Financial services firms face a significant cyber insurance coverage gap, as well as growing threats related to climate, geopolitics and technology. Here’s how to tackle the risks

Spotlight on: product recall risks

As data shows that recalls are increasing across food, consumer products and automotive, we look at what risk managers can learn from the past and how to minimise the threats for the future

Global tensions are rising, but risk perceptions are in the eye of the beholder

To successfully separate threats from opportunities risk managers must first understand the role of perception in the identification of risk. Zurich’s John Scott discusses the big picture

How risk professionals can find a path through the web of interconnected threats

Companies must accelerate their response to a more pervasive and complex risk environment and take steps to reinvent risk management. Here’s how

Key risk management lessons from the top ten cyber attacks in 2023

Nation-state attacks, ransomware, and data breaches feature among the most catastrophic cyber incidents in 2023. Here are the lessons that risk professionals must learn to protect their businesses

Movers and Shakers - Bloomberg, Saxo Bank, Evelyn Partners, Zurich, WTW, Gallagher

The latest appointments news from across the global risk, broking and insurance industries